CSC8503 Average Heist of the Golden Goose

Video link:Grade: 100%

Summary

CSC8503 was a module focused on programming physics, networking and AI into a game in C++. The main features of my game were:

Physics

- Collisions for Sphere-Sphere , Sphere-AABB, Sphere-OBB, AABB-AABB, Capsule-Sphere, Capsule-AABB

- Ray collisions for all types.

- Physics materials with changeable coefficient of restitution, vertical damping and horizontal damping.

- Collision layers so objects can ignore collisions with each other.

- Raycast collision layers.

- Quad tree broad phase for faster processing.

- Static and dynamic objects, where collisions between static objects are not considered.

- Sleeping and awake objects, where collisions between sleeping objects are ignored, and static objects are also ignored.

- A grappling hook that uses raycasts to allow the player to grapple towards static objects, and pull dynamic objects towards them.

- Trigger volumes used for a jump pad, and used to allow the player to pick up and throw objects when the trigger is over a dynamic object.

AI

- A state machine enemy that will patrol between points, run towards the player if it can see them, shoot the player if it is close enough, pathfind to get to the player if it cannot see them, and then return to patrolling if the player hides for long enough.

- Pathfinding that can be executed multiple times by the enemy to navigate the world.

- A simple behaviour tree powered enemy that stays near the treasure and provides resistance when it detects that the player is trying to steal the treasure, until it eventually gives up.

- Both of these enemies work in single player and in multiplayer, where they are controlled by the server in multiplayer.

- Pushdown automata used for the main menu, including the ability to pause the game in singleplayer.

Networking

- The game can be started as a client or a server.

- When the player joins a server, the server sends a message to all players and the correct number of player objects are added.

- Player inputs are sent to the server and processed.

- The server executes all physics, and the results are sent to the clients.

- Game information such as player health and points are sent from the server to the clients when events occur that change those values.

Other

- Simple component system for easily adding functionality to game objects. This is not a full Entity Component System but for the purposes of the coursework it is sufficient.

Extensions of the tutorials

Similarly to CSC8502, some of this was covered in tutorial content, and the main extensions were:

- Various physics engine improvements, with physics materials, static and dynamic objects, object sleeping, collision layers and trigger volumes.

- A complete state machine based enemy, which uses pathfinding to chase the player and attack them.

- Basic implementation of networking, to a degree that was not covered in the tutorials.

Physics

The codebase for the coursework included some physics code already, and following the tutorial content led to working Axis Aligned Bounding Box, plane, and sphere collisions, with raycast checks for all of these also implemented. The missing collisions were Oriented Bounding Boxes against AABBs, spheres and capsules, and capsule-capsule collisions.

The implementation of capsules was very minimal to start off with, and I managed to implement AABB-Capsule, Sphere-Capsule, OBB-Capsule and Sphere-OBB, but not OBB-Capsule or Capsule-Capsule.

There were some physics features that I was aware were standard, but were missing from the engine. I knew about these features mainly because of their inclusion in the Unity game engine, and I decided to implement them myself, to the best of my knowlege.

For Physics materials, I made a simple struct which stored coefficient of restitution, and a few different damping values for extra control over how physics objects behaved.

struct PhysicsMaterial

{

float e;

float linearDampHorizontal;

float linearDampVertical;

float angularDamp;

};

PhysicsMaterial struct.

PhysicsObjects in the game store a pointer to a PhysicsMaterial, so when updating the game’s physics, these values can be retrieved and used to modify the result. My main reason for splitting linear damping into vertical and horizontal was to fine tune the player’s controls: by damping more horizontally, the player comes to a stop faster when moving, resulting in controls that feel less slippery. Damping vertical velocity seperately means I could tweak the player’s movement without altering how their jump performed.

Picking Up Objects

In my game, I wanted the player to be able to pick up objects and carry them around, to allow for physics puzzles in my game. This mechanic was very much inspired by the Source engine, and the games made in it such as Half Life 2 and Garry’s mod. To allow the player to pick up objects, there needed to be a way to detect what objects the player could pick up. There were 3 ways I thought to do this:

- Raycast from the camera and if the ray hits an object that can be picked up, and the player is close enough, then pick it up. This would make picking up objects very precise and might be frustrating.

- Get all of the objects that are close to the player, and if one is close enough, then pick it up. This could lead the player to pick up objects they did not want to pick up.

- Have a sphere collider a fixed distance away from the player that moves as the player looks around, and if this is colliding with an object that can be picked up, then pick it up.

I opted to go for the third option, as this was the most sensible and would feel the best for the player.

Vector3 ObjectPickupComponent::CalculateLookDirection() {

float camYaw = camera->GetYaw();

float camPitch = camera->GetPitch();

float normYaw = camYaw > 180 ? camYaw - 360 : camYaw; //get yaw between -180 and 180

normYaw = normYaw * DEGREES_TO_RAD;

//convert from pitch/yaw to directions

float xDir = cos(normYaw) * cos(camPitch * DEGREES_TO_RAD);

float yDir = sin(camPitch * DEGREES_TO_RAD);

float zDir = sin(-normYaw) * cos(camPitch * DEGREES_TO_RAD);

return Vector3(zDir, yDir, -xDir);

}

Converting from camera pitch and yaw values into a Vector3 direction. The trigger is then offset by a multiple of this vector.

To make an object “picked up”, a constant force is applied towards the centre of this pickup trigger, which is proportional to distance. Through a simple Hooke’s Law calculation, it was relatively easy to make picking up objects feel good for the player. I wanted it to still feel slightly springy, to convey a feeling of weight in the objects. After some tweaking, I decided on another improvement: changing an object’s PhysicsMaterial while picking it up, and swapping it back afterwards. The reason I did this was because I wanted objects that were picked up to move faster but slow down much quicker, so I increased the force being applied but also increased the damping in a new PhysicsMaterial.

The player can pick up and throw objects.

Another physics-based mechanic I added to the game was a grapple hook. For this, I wanted it to behave differently depending on if the player grappled a static wall or a dynamic object. If they grapple a wall, they should be pulled towards it, if they grapple an object, the object should be pulled to them. To do this, I raycast from the player and check the type of the object hit. If its static, then the point the raycast hit is used as the anchor point and the player constantly applies a force towards it. If it is dynamic, a constant force is applied to the centre of the object towards the player.

The player can grapple objects towards them.

AI

For the AI of the game, I decided that I should add only 2 enemies: one using a state machine, one using behaviour trees. Both of these techniques were covered in the tutorial content, but not to a degree that resulted in an enemy.

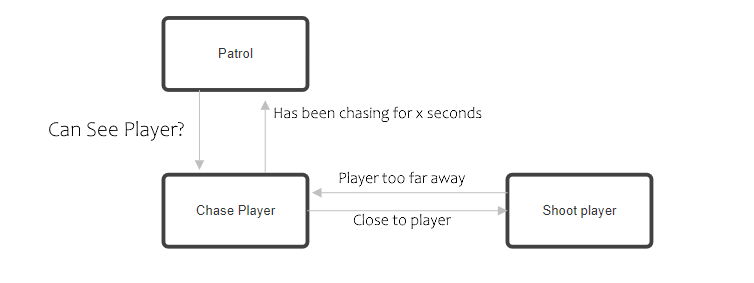

For my state machine enemy, I wanted it to behave like a very simple, FPS style enemy: patrol between points until it sees the player - > chase the player until they are close enough - > shoot the player.

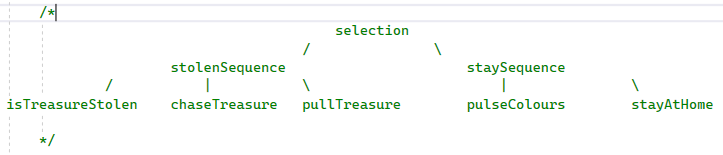

State Machine diagram for the enemy.

The enemy cannot be killed as they have no health and the player has no attack: they are simply an obsticle to avoid. I could have added this ability, but I wanted the enemy to always have presence. A key part to make this enemy function was to integrate pathfinding into the state machine: if the enemy is chasing the player but cannot see them, then they must navigate around walls in the level to see them. Thankfully, my level was all block based, and as such setting nodes in the graph for pathfinding was very easy. Any space that did not have a block was traversable by the enemy. The enemy only performs an A* search if the player has moved at least 1 block away from the enemy’s current goal node, as only then could the player has possibly moved to a new area.

State machine enemy chasing and shooting the player.

The behaviour tree enemy is not really an enemy: they are even more of an obsticle than the state machine enemy. They have these behaviours: hover in the air, pull back the treasure, or return to their start point.

The behaviour tree uses a combination of selectors and sequences.

By having an isTreasureStolen node as the first action in the left sequence, the whole sequence will fail if the treasure has not been stolen, and therefore the root selector will perform the right subtree.

These enemies are very simplistic, but still provided further interest and challenge for the player.

Networking

The networking part of this project was definitely the messiest part, as I created the rest of the game without networking in mind, thinking I would not have the time to get round to it. However, I decided to give it a go anyway, and although it resulted in a codebase I am not very happy with, the result was functional and playable between multiple instances on the same localhost. So far in the coursework, I just had the singleplayer game handle all processing, including physics and AI. However, when moving to networking, I decided to delagate these things to the server instead, as this is the typical approach to make sure the objects on all clients match up in a real time game. For networking, I had a few different types of packets which were used between clients and servers:

- FullPacket. This sends the data of an object in that game that should have its physics networked (position and orientation). The server sends these to clients after processing physics.

- ClientPacket. This is sent from the client to the server, and contains inputs from the client. This is in the form of a

bool[8], with each element representinf if a button is pressed or not. - GameInfoPacket. This is sent from server to client and contains health, points and collectables of a specific player.

- PlayerConnectPacket. This is a packet that is sent from client to server when the client joins the server, so the server knows a player has successfully connected.

- PlayerConnectServerAckPacket. This packet is sent from server to all clients once the server receives a PlayerConnectPacket. It lets all the clients know how many players are currently connected, so the newly joined client can create the correct number of player objects, and the old clients can create a new player and assign the correct networkID.

struct ClientPacket : public GamePacket {

int objectID;

bool buttonstates[8];

//buttonstates[0] = W

//buttonstates[1] = A

//buttonstates[2] = S

//buttonstates[3] = D

//buttonstates[4] = Space

//buttonstates[5] = Right Click

//buttonstates[6] = Left Click

//buttonstates[7] = E

float camPitch;

float camYaw;

ClientPacket() {

type = Client_State;

size = sizeof(ClientPacket) - sizeof(GamePacket);

}

};

ClientPacket, that sends inputs from client to server.

I store the player inputs in a map structure, with a key of the networkID of the player and the values being a bool[8]. This way, each client’s inputs from the last packet are stored and can be used in game functionality.

void TutorialGame::ProcessClientInput(ClientPacket* p) {

playerInputsMap[p->objectID][0] = p->buttonstates[0];//w

playerInputsMap[p->objectID][1] = p->buttonstates[1];//a

playerInputsMap[p->objectID][2] = p->buttonstates[2];//s

playerInputsMap[p->objectID][3] = p->buttonstates[3];//d

playerInputsMap[p->objectID][4] = p->buttonstates[4];//space

playerInputsMap[p->objectID][5] = p->buttonstates[5];//left click

playerInputsMap[p->objectID][6] = p->buttonstates[6];//right click

playerInputsMap[p->objectID][7] = p->buttonstates[7];//e

playerCameraMap[p->objectID].pitch = p->camPitch;

playerCameraMap[p->objectID].yaw = p->camYaw;

}

Method to process the data from a client packet. playerInputsMap is used to move the player objects.

With these packets, most of my game functioned the same in multiplayer. There were some missing features however, as if an object is destroyed in the server (such as a door being opened), there is no packet to tell the clients to delete it, and therefore the clients still render the object. I created a DisableObjectPacket, but did not have time to implement the sending and receiving of it.

Two clients in the same game.

Simple Components

The initial codebase for the project was not very easy to work with when it came to adding functionality to objects in the game, so I added my own component system. This was a very naive implementation, and was in no way a true Entity Component System as there was no notion of contiguous memory or an entity-component registry. I simply added a new base class, Component.h, with some easy to understand virtual functions:

class Component

{

public:

Component() { };

~Component() {};

Component(GameObject* gameObject) { this->gameObject = gameObject;}

virtual void Update(float dt) {};

virtual void PhysicsUpdate(float dt) {};

virtual void Start(GameWorld* gw) {};

virtual void OnCollisionBegin(GameObject* otherObject) {};

virtual void OnCollisionStay(GameObject* otherObject) {};

virtual void OnCollisionEnd(GameObject* otherObject) {};

protected:

GameObject* gameObject;

};

The heavy use of virtual functions is obviously not the most efficient approach to object functionality, due to the added vtable lookups, but for the purposes of the coursework it provided a very easy way to make objects in my game do things. The methods of the class are heavily inspired by Unity’s MonoBehaviour methods, and I wanted them to be used in basically the exact same way: Update() called every frame, PhysicsUpdate() called every time physics was updated, and so on.

To call these functions, the GameObject class was extended to store a vector of Components. GameObject will iterate through each component and call the appropriate virtual function whenever it is necessary, and as such, each component gets a chance to call their code. Making new functionality involved subclassing Component and overriding the necessary methods, then instantiating it and linking it to a GameObject when the GameObject was created.

What went well

I am quite happy with how my player movement felt, as it behaved very much like how you would expect a first person controller in a normal video game to. My pickup mechanic was also good and was close to how I envisioned it when I thought of the idea. Although my networking was not very impressive and was missing many features, I am still very happy with the extent that it functioned, considering I implemented it in only a few days. I am especially happy with the fact I managed to handle players joining the game for all current players.

What I would improve

My weakest aspect in this module was definitely my implementation of collision detection for the various volumes. My lack of OBB collision detection makes the physics feel very simple, even though it was not required for the game to be playable. Having OBB-Capsule at least allows for the player to run up ramps which is important. Another big area that my physics was lacking was no friction, meaning when objects collided with eachother, they would not rotate. This is something I would have really liked to implement, but I did not want to spend too much time on the physics as, at the time, I still had the AI and networking parts of the coursework to implement.

The gameplay loop was also very weak and simple.

The networked aspect of the game was functional only on a local host, though there was no expectation of the coursework to run across multiple machines. Furthermore, my networking was done using full packets only, instead of the much more efficient delta packets. This was purely a time constraint as I could have figured out how to implement both full and delta packets given a few more days.

Code Samples

StateMachineEnemyComponent::StateMachineEnemyComponent(GameObject* g, std::vector<Vector3> pp) {

gameObject = g;

counter = 0.0f;

stateMachine = new StateMachine();

patrolPoints = pp;

State* patrolState = new State([&](float dt)->void {this->Patrol(dt); });

State* chasePlayerState = new State([&](float dt)->void {this->ChasePlayer(dt); });

State* shootPlayerState = new State([&](float dt)->void {this->ShootPlayer(dt); });

State* returnToPatrolState = new State([&](float dt)->void {this->ReturnToPatrol(dt); });

stateMachine->AddState(patrolState);

stateMachine->AddState(chasePlayerState);

stateMachine->AddState(shootPlayerState);

stateMachine->AddTransition(new StateTransition(patrolState, chasePlayerState,

[&]()->bool {

return canSeePlayer;

}));

stateMachine->AddTransition(new StateTransition(chasePlayerState, shootPlayerState,

[&]()->bool {

float distance = (playerObject->GetTransform().GetPosition() - gameObject->GetTransform().GetPosition()).Length();

return canSeePlayer && distance <= SHOOT_PLAYER_DISTANCE;

}));

stateMachine->AddTransition(new StateTransition(shootPlayerState, chasePlayerState,

[&]()->bool {

float distance = (playerObject->GetTransform().GetPosition() - gameObject->GetTransform().GetPosition()).Length();

return !canSeePlayer || distance >= CHASE_PLAYER_DISTANCE;

}));

stateMachine->AddTransition(new StateTransition(chasePlayerState, returnToPatrolState,

[&]()->bool {

return !canSeePlayer && losePlayerTimer > CHASE_PLAYER_TIME;

}));

stateMachine->AddTransition(new StateTransition(returnToPatrolState, patrolState,

[&]()->bool {

float distance = (patrolPoints[currentPatrolPoint] - gameObject->GetTransform().GetPosition()).Length();

return distance < PATROL_RETURN_DISTANCE;

}));

stateMachine->AddTransition(new StateTransition(returnToPatrolState, chasePlayerState,

[&]()->bool {

return canSeePlayer;

}));

}

Because of my component system, making objects interact was relatively easy. Here is the pickup that unlocks the player's grappling hook (UnlockGrappleComponent.cpp):

void UnlockGrappleComponent::OnCollisionBegin(GameObject* other) {

if (other->GetTag() == "Player") {

PlayerInputComponent* pic;

if (other->TryGetComponent<PlayerInputComponent>(pic)) {

pic->UnlockGrapple();

}

}

}

This function is used when the player grapples, and it checks if the grapple hit a static or dynamic object.

void PlayerInputComponent::BeginGrapple()

{

Vector3 lookDir = CalculateLookDirection();

Ray ray(gameObject->GetTransform().GetPosition() + Vector3(0, 0.3f, 0), lookDir);

RayCollision rc;

if (worldRef->Raycast(ray, rc, true, raycastCollideMap, gameObject)) {

if (((GameObject*)rc.node)->GetPhysicsObject()->IsDynamic()) {

grappledObject = (GameObject*)rc.node;

isGrapplingStatic = false;

}

else {

staticGrapplePoint = rc.collidedAt;

isGrapplingStatic = true;

}

isGrappling = true;

}

}

The PhysicsUpdate handles any forces in the PlayerInputComponent.

void PlayerInputComponent::PhysicsUpdate(float dt) {

if (hasJumped) {

gameObject->GetTransform().SetPosition(gameObject->GetTransform().GetPosition() + Vector3(0, .1f, 0));

physObject->ApplyLinearImpulse({ 0,jumpPower,0 });

}

hasJumped = false;

if (isGrappling) {

if (isGrapplingStatic) {

GrappleStatic();

}

else {

GrappleDynamicObject();

}

}

}

These are the functions that handle the forces related to the grappling hook.

void PlayerInputComponent::GrappleStatic()

{

Debug::DrawLine(gameObject->GetTransform().GetPosition(), staticGrapplePoint);

if (hasUnlockedGrapple) {

Vector3 forceDirection = staticGrapplePoint - gameObject->GetTransform().GetPosition();

forceDirection.Normalise();

forceDirection.y *= 0.3f; //this helps make the grapple feel more like a swing

physObject->AddForce(forceDirection * STATIC_FORCE);

}

else {

Debug::Print("Grapple Not Strong Enough!", { 30,80 });

}

}

void PlayerInputComponent::GrappleDynamicObject()

{

Debug::DrawLine(grappledObject->GetTransform().GetPosition(), gameObject->GetTransform().GetPosition());

Vector3 forceDirection = gameObject->GetTransform().GetPosition() - grappledObject->GetTransform().GetPosition();

forceDirection.Normalise();

grappledObject->GetPhysicsObject()->SetAwake();

grappledObject->GetPhysicsObject()->AddForce(forceDirection * DYNAMIC_FORCE);

}

These actions are used for the enem using a behaviour tree.

BehaviourAction* pullTreasure = new BehaviourAction("Pull Treasure",

[&](float dt, BehaviourState state)->BehaviourState {

Vector3 pullDirection = (gameObject->GetTransform().GetPosition() - treasure->GetTransform().GetPosition()).Normalised();

treasurePhys->SetAwake();

treasurePhys->AddForce(pullDirection * PULL_TREASURE_AMOUNT *dt);

return Success;

}

);

BehaviourAction* isTreasureStolen = new BehaviourAction("Is Treasure Stolen",

[&](float dt, BehaviourState state)->BehaviourState {

if ((treasure->GetTransform().GetPosition() - treasureStartPoint).LengthSquared() > DISTANCE_BEFORE_STOLEN) {

return Success;

}

else {

return Failure;

}

}

);

BehaviourAction* pulseColours = new BehaviourAction("Pulse Colours",

[&](float dt, BehaviourState state)->BehaviourState {

colourTimer += dt;

float colourMult = (sin(colourTimer) + 1) * 0.5f;

Vector4 colour = Debug::RED * colourMult + Debug::BLUE * (1 - colourMult);

gameObject->GetRenderObject()->SetColour(colour);

return Success;

}

);

BehaviourAction* stayAtHome = new BehaviourAction("Stay At Home",

[&](float dt, BehaviourState state)->BehaviourState {

Vector3 direction = (homePoint - gameObject->GetTransform().GetPosition()).Normalised();

thisPhys->AddForce(direction * PULL_TREASURE_AMOUNT * dt);

return Success;

}

);

BehaviourAction* chaseTreasure = new BehaviourAction("Chase Treasure",

[&](float dt, BehaviourState state)->BehaviourState {

if( (homePoint-treasure->GetTransform().GetPosition()).LengthSquared() >CHASE_DISTANCE)

return Failure;

Vector3 direction = (treasure->GetTransform().GetPosition() - gameObject->GetTransform().GetPosition()).Normalised();

thisPhys->SetAwake();

thisPhys->AddForce(direction * PULL_TREASURE_AMOUNT * dt);

return Success;

}

);

For my PhysicsSystem's collision layer system, it references this matrix for if two objects should collide.

enum CollisionLayers

{

DEFAULT_LAYER = 1, PLAYER_LAYER = 2, STATIC_LAYER = 4, PICKUP_SPHERE_LAYER = 8

};

class PhysicsSystem{

//...

std::map<int,bool> layerMatrix =

{ {DEFAULT_LAYER | DEFAULT_LAYER,true},

{DEFAULT_LAYER | PLAYER_LAYER,true},

{DEFAULT_LAYER | STATIC_LAYER,true},

{DEFAULT_LAYER | PICKUP_SPHERE_LAYER,true},

{PLAYER_LAYER | PLAYER_LAYER,true},

{PLAYER_LAYER | STATIC_LAYER,true},

{PLAYER_LAYER | PICKUP_SPHERE_LAYER,false},

{STATIC_LAYER | STATIC_LAYER,false},

{STATIC_LAYER | PICKUP_SPHERE_LAYER,false},

{PICKUP_SPHERE_LAYER | PICKUP_SPHERE_LAYER,false}

};

}

These are some networking related functions for handling packets being received.

void TutorialGame::ReceivePacket(int type, GamePacket* payload, int source) {

if (isClient) {

ReadPacketClient(type, payload);

}

else {

ReadPacketServer(type, payload, source);

}

}

void TutorialGame::ReadPacketServer(int type, GamePacket* payload, int source){

switch (type) {

case Client_State: {

ClientPacket* realPacket = (ClientPacket*)payload;

ProcessClientInput(realPacket);

break;

}

case Player_Connected: { //this means a client is sending a connect message

ProcessServerPlayerConnectPacket(source, payload);

break;

}

}

}

void TutorialGame::ReadPacketClient(int type, GamePacket* payload)

{

switch (type) {

case Full_State: {

ProcessClientFullPacket(payload);

break;

}

case Player_Connected: { //if we recieve this, it tells us a new player has connected (could be this client)

ProcessClientPlayerConnectedPacket(payload);

break;

}

case Game_info: {

ProcessClientGameInfoPacket(payload);

break;

}

}

}

Here are some of the functions used above.

void TutorialGame::ProcessClientPlayerConnectedPacket(GamePacket* payload)

{

if (!hasClientInitialised) { //this means that this game is a new client and objects for all current players are needed

PlayerConnectServerAckPacket* realPacket = (PlayerConnectServerAckPacket*)payload;

AddPlayerToWorld(Vector3(80, 0, 10), true, false, true, realPacket->playerNetIDs[realPacket->numPlayers - 1]);

for (int i = 0; i < realPacket->numPlayers - 1; i++) {

AddPlayerToWorld(Vector3(80, 0, 10), true, false, false, realPacket->playerNetIDs[i]);

}

hasClientInitialised = true;

}

else { //this means a new player has joined the game and a new player object is needed

PlayerConnectServerAckPacket* realPacket = (PlayerConnectServerAckPacket*)payload;

AddPlayerToWorld(Vector3(80, 0, 10), true, false, false, realPacket->playerNetIDs[realPacket->numPlayers - 1]);

}

}

void TutorialGame::ProcessServerPlayerConnectPacket(int source, GamePacket* payload)

{

if (prevClient == source)return; //if we receive lots of packets from the same client, ignore them and only send one packet back

PlayerConnectPacket* realPacket = (PlayerConnectPacket*)payload;

numPlayers++;

GameObject* player = AddPlayerToWorld(Vector3(80, 0, 10), true, true);

playerObjects.push_back(player);

GamePacket* p;

playerIDs[numPlayers - 1] = currentNetworkObjectID - 1;

PlayerConnectServerAckPacket* pac = new PlayerConnectServerAckPacket();

pac->numPlayers = numPlayers;

pac->playerNetIDs[0] = playerIDs[0];

pac->playerNetIDs[1] = playerIDs[1];

pac->playerNetIDs[2] = playerIDs[2];

pac->playerNetIDs[3] = playerIDs[3];

server->SendGlobalPacket(*pac); //tell all clients a new player has joined

prevClient = source;

}