Goo Surge (Pirate Software Game Jam 2024)

Video link:Game thumbnail art by Erick (click for link)

Play the Game

Summary

Goo Surge was a game made in two weeks by me and 3 of my coursemates on the Newcastle University Games Engineering Course. We had a large gap between Christmas and returning to university, so we decided to make productive use of our time and do a game jam together. We decided upon the Pirate Software Game Jam as the dates lined up well, and doing a 2 week game jam gave us much more time to get used to working with eachother and setting up the project.

When starting the jam, we agreed that we wanted to focus on making something interesting from a technical standpoint, and to challenge ourselves to do something we hadn’t programmed before. The game uses Compute Shaders to process the spreading and temperature of millions of tiles of goo, which can burn and destroy objects and walls in the level, at a playable framerate.

The game was overall successful, with the main flaw being the lack of tutorial and the general confusion players felt when trying to know what to do next. Some key information about the project:

- Worked in a team of 4 programmers.

- Compute shaders used to process millions of pixels at a playable framerate.

- Hundereds of objects checking for goo with little performance impact.

- Destructable, tile-based level.

- Drawing mechanic and symbol recognition to cast spells.

- Usage of observer pattern for modular functionality.

- I participated in some paired programming with another team member to improve the quality of code and find bugs faster.

- Complete game loop with main menu, win/loss screens and credits.

- Smooth controls and camera.

- Original music and sound effects.

Gameplay

The player controls a wizard who has been tasked to break out the imprisoned goo, steal schematics and destroy as much of the facility as they can. Our main gameplay mechanic was the goo. In our game, there is an ever expanding pool of goo, which spreads throughout the level, and the player can alter its properties by either heating it up (making it faster and more destructive) or cooling it down (making it slower and safer). When the goo is hot, it can destroy objects and walls in the level, giving the player points and opening up new areas of the level, but it can also hurt the player, so they need to be careful.

Goo that has been cooled, making it expand slower

Drawing runes

The supporting mechanic of our game was rune drawing. In order to cast a spell, the player must open their canvas and draw the corresponding rune correctly. This adds an extra element of difficulty to the game and makes the game feel more frantic.

Casting different spells is done by drawing different symbols.

The rune drawing mechanic was not programmed by me, instead being made by Alex (click for link). Because of this, I do not know all the technical details on how it works. From a gameplay standpoint, the mechanic was a good addition to the game, as it added some extra challenge and tension. However, it also added frustration for the player when they thought they drew a rune correctly, only for the game to not recognise it.

The Goo

Data

We decided early on that the main way the player would interact with the goo would be by heating it up. As such, we knew we needed a way to both store the temperature on a per pixel basis, and to run code on each tile of goo every time we wanted to update it. With a technical challenge such as this, we agreed that we had do these calculations on the GPU, as this was a very parallel problem. Therefore, we decided to attempt to do this using Compute Shaders, something none of us had never done before. My and my teammate Ben (click for link) were responsible for the goo mechanics in the game, whilst our other team members Alex (click for link) and Erick (click for link) worked on the Rune Drawing and Tile Grid mechanics respectively. To store the information for the goo, we decided to use a texture instead of a buffer. This was for a few reasons.

Firstly, textures are easy data containers to use with shaders, as there is very little manual setup: Unity’s Compute Shaders by default use RenderTextures. Secondly, we knew that the number of types of data would match up with the number of texture channels: one channel for the type of goo, one channel for temperature of the goo, one channel to track how long until a goo tile spreads, and one channel for a target temperature for the goo to reach over time.

public enum GridChannel

{

TYPE,TEMP,GOOAGE,TARGET_TEMP

}

Enum used when interacting with different channels of the goo texture.

This did mean however that we were wasting bandwidth slightly when sending a texture. For example, the “TYPE” channel should only ever have 1 of 4 values, and therefore storing it in a float (the type that our texture used for it’s channels) is slightly wasteful. We decided this tradeoff was worth it for the ease of use.

public enum GridTileType

{

BLANK,GOO_SPREADABLE,GOO_UNSPREADABLE,STATIC,MAX_TYPE

}

Enum used for the different types of pixels.

The final big advantage was that it would be very easy to render the goo to the screen. Since the goo data is stored in a texture, all we needed to to was to apply that texture to a quad, and create a custom fragment shader to convert from goo data into a visual representation. To do this, I made a new fragment shader that will interpolate between three colours: one hot, one normal, and one cold. The temperature value is squared such that changes in temperature are shown more drastically when the goo is hot. Additionally, any pixel that has the type “STATIC” or “BLANK” will have the alpha value set to 0, so when rendered, the pixel is not visible.

if (data.y <= 0.5f)

{

colour = lerp(coldTemp, normalTemp, (data.y * 2) * (data.y * 2));

}

else

{

colour = lerp(normalTemp, hotTemp, ((data.y - 0.5f) * 2) * ((data.y - 0.5f) * 2));

}

Snippet from the fragment shader used to convert from goo data to visuals. data.y is the temperature value of the pixel.

We could have instead used a Compute buffer (which we originally started using), but switched to a texture relatively quickly.

Instead of calling the shader every frame (which could very easily become inconsistent) we decided to utilise Unity’s coroutine system, to have a coroutine that updates the goo every 0.05 seconds. Unity’s support for compute shaders was very intuitive, and this was our function to dispatch the compute shader:

IEnumerator UpdateGoo()

{

WaitForSeconds wfs = new WaitForSeconds(0.05f);

cs.SetInt("aspectX", xSize);

cs.SetInt("aspectY", ySize);

while (active)

{

cs.SetTexture(0, "Result", renderTexture);

cs.Dispatch(0, renderTexture.width / 16, renderTexture.height / 16, 1);

GetGooDataFromGPU();

yield return wfs;

}

}

Spreading goo

To make the goo spread, we made some rules, in a similar way to Conway’s Game Of Life:

- Goo can only spread to empty pixels.

- Goo can only spread when its “GOOAGE” is at maximum.

- Only pixels that are “GOO_SPREADABLE” can spread.

- Once a pixel has spread, it becomes “GOO_UNSPREADABLE”.

- Hotter pixels spread faster than cold ones.

- When spreading, new goo pixels will have a slightly more normal temperature than the pixel it spread from.

All of this logic was handled in one compute shader, which applies these rules to every pixel each time the shader is ran.

void Spread(uint3 id)

{

float4 values = Result[id.xy];

values.x = 2.0f/255.0f; //Set type to GOO_UNSPREADABLE

Result[id.xy] = values;

values.x = 1.0f/255.0f;//Set type to GOO_SPREADABLE

values.z = 0.0f;

values.y -= 1.0f *values.x; //Reuse values.x and reduce temperature

float2 temp = id.xy;

//pixel to the right

temp.x += 1;

if (temp.x < aspectX && Result[temp.xy].x == 0)

{

Result[temp.xy] = values;

}

//pixel to the left

temp.x -= 2;

if (temp.x >= 0 && Result[temp.xy].x == 0)

{

Result[temp.xy] = values;

}

//pixel above

temp.x += 1;

temp.y += 1;

if (temp.y < aspectY && Result[temp.xy].x == 0)

{

Result[temp.xy] = values;

}

//pixel below

temp.y -= 2;

if (temp.y >= 0 && Result[temp.xy].x == 0)

{

Result[temp.xy] = values;

}

}

Snippet of compute shader code to spread goo to 4 adjacent tiles, with slightly lower temperature.

The reason that we have the value 2.0f/255.0f in here is due to conversions that occur between the CPU and GPU: on the CPU, our values range from 0-255 per channel, but the GPU deals with numbers normalised to be in the range 0.0f-1.0f. Therefore, any calculations we do in the shader that we want to be the same on the CPU must be divided by 255.0f to get them in the range 0.0f-1.0f.

Balancing temperature

Spreading goo is an important mechanic, but with just this, the temperature of a goo pixel would never change over time. Furthermore, if the player heats up a pixel of goo, then goo tiles around it should also heat up. We therefore had a secondary EntropyShader.compute which handles distribution of heat and the cooling down of goo.

The goo constantly tends towards a middle temperature, done using a TARGET_TEMPERATURE channel. The temperature of the goo will tend towards this temperature, and then the target temperature will tend towards a value of 0.5f. This way, the player can control the target temperature of the goo to keep it hotter / cooler for longer, but it will always return to a base temperature.

EntropyShader reducing the temperature of the hot goo and blurring it.

EntropyShader increasing the temperature of the cold goo and blurring it.

Another feature of the EntropyShader is temperature blurring. Over time, temperature values will blur together and affect nearby pixels. To do this, each pixel calculates the average temperature of a 5x5 area around it, and then sets its target temperature to this temperature. That way, hot pixels in cold areas will cool faster, and vice versa.

void HeatConduction(uint3 id)

{

float4 values = Result[id.xy];

float targetTotal = 0;

int count = 0;

for (int i = -5; i < 6; i++)

{

for (int j = -5; j < 6; j++)

{

float2 temp = { i, j };

if (Result[id.xy + temp].x * 255 >= 1.0f && Result[id.xy + temp].x * 255 <= 2.0f)

{

count++;

float temperature = Result[id.xy + temp].y;

targetTotal += temperature;

}

}

}

values.w = targetTotal/ count;

Result[id.xy] = values;

}

Snippet of compute shader code to blend temperatures across the texture.

Checking for Goo

Objects in the game need some way of knowing if they are touching hot goo, so they can take damage and be destroyed. In out game, we had 2 types of objects:

- Static. Static objects are fixed to the grid, and are either walls or doors. These objects impede the flow of goo until they are destroyed, at which point it allows for goo to spread again.

- Dymanic. Dynamic objects are not fixed to the grid and do not block goo, but can still take damage from hot goo.

Static objects must check the pixels adjacent to them in order to see if there is hot goo. We decided that this could be too inefficient if done every frame, so we placed this in a coroutine to check every second. Whenever a static object runs out of health, it needs to write to the pixels it takes up and set them to be “BLANK”, so goo can flow again. Furthermore, the goo tiles need to be set to “GOO_SPREADABLE” so the shader makes them spread again. This means that statics must be able to write to the GPU side texture.

Dynamic objects are much easier, as they are not fixed to the tile grid, not do they have any presence on the RenderTexture. As such, they only need to read data from the CPU side texture. Since we knew we were going to have many dynamic objects in the game, we opted to have dynamic objects only check one row of pixels, starting at the bottom of the sprite, as this is also a logical place for where they would take damage.

Hot goo destroying some computer desks.

Checking dynamic objects is not done by the objects themselves, but instead by the Level object, which holds a reference to all dynamic objects in the scene. The main benefit of this is improved cache use, as the large goo texture only needs to be loaded into cache once before all dynamics are checked against it, resulting in the ability to check hundereds of dynamic objects every frame.

void UpdateDynamics()

{

foreach (DynamicDestructable o in dynamicDestructables)

{

if (!o.active) continue;

for (int i = 0; i < o.GetWidth(); i++)

{

float type = gooController.GetTileValue(o.GetGooPos().x + i, o.GetGooPos().y - 1, GridChannel.TYPE);

if (type == (float)GridTileType.GOO_SPREADABLE || type == (float)GridTileType.GOO_UNSPREADABLE)

{

float gooTemp = gooController.GetTileValue(o.GetGooPos().x + i, o.GetGooPos().y - 1, GridChannel.TEMP);

if (gooTemp > gooTempThresholdDynamics)

{

o.GooDamage(gooTemp - gooTempThresholdDynamics);

break;

}

}

}

}

}

We were initially worried how well this part of the game would perform, but it turned out to actually be the static objects that had the most performance impact, which I will discuss in the next section.

Performance limitations

Our main performance bottlenecks were not actually related to the speed of execution of the compute shaders: these had very little impact on the game. The main problem was sending data between the GPU and the CPU, as there needed to be consistency between the CPU side texture and the GPU side texture. The reason for this is that although all goo spreading and temperature logic was handled in the Compute Shader (GPU) any objects in the game such as walls, desks or tables needed to be able to check for hot goo, such that they could take damage.

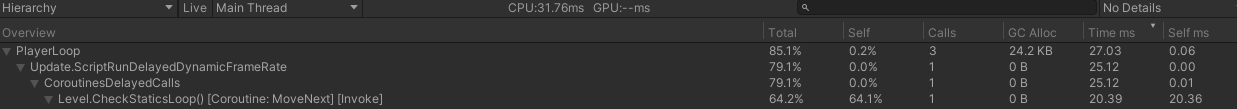

Throughout the project, I used Unity’s profiler regularly to find which functions and parts of our code were being particularly slow.

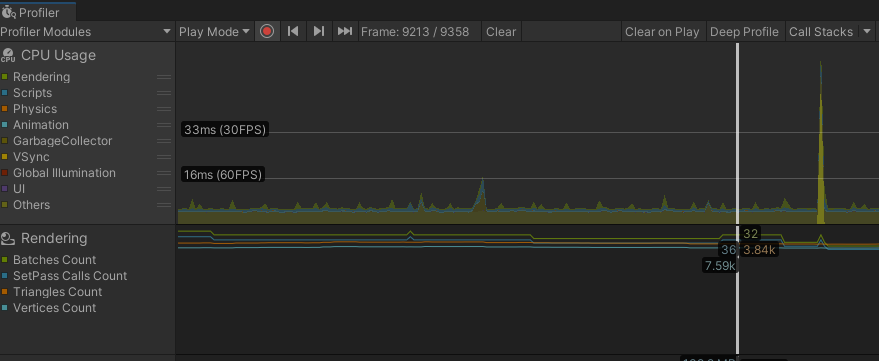

For example, I noticed that when first releasing the goo, the game would stutter quite badly:

A large dip in framerate.

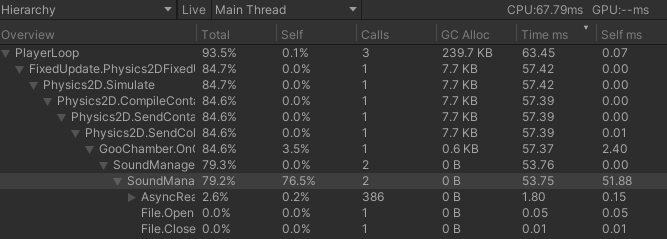

Upon looking at this in the profiler, the cause of the issue was actually the audio:

The cause of the issue was related to audio.

The reason for this was that the game was loading the sound effect for the siren into memory when the player released the goo, instead of loading it to memory to start with. I therefore enabled “Load in background” on the audio clip, and the problem was fixed.

In general, the largest performance issue was stuttering that occurs when all of the static objects in the scene check for goo:

At 1 second intervals, the game would stutter when checking statics.

Unfortunately, we did not have enough time to fix this stutter, but the code causing the stutter was related to checking the texture for goo touching each static. I think the reason for this is misuse of cache: the scope of functions for checking statics was different to that of dynamics, and I think that the cache was not expoited in the same was as a result. Checking statics does check drastically more pixels (each wall tile checks 32 pixels that touch it, as opposed to a maximum of 16 pixels for dynamics), but there should not the that wide of a gap in performance.

What went well

On a technical level, I am very happy with what we managed to achieve as a team. For never having used compute shaders before, the game uses them appropriately and still operates at a very playable framerate. For my first time in a project with other programmers, I thought that we worked very well together and we managed to get our code working together quite easily, thanks to good planning and organisation at the start of the project.

What I would improve

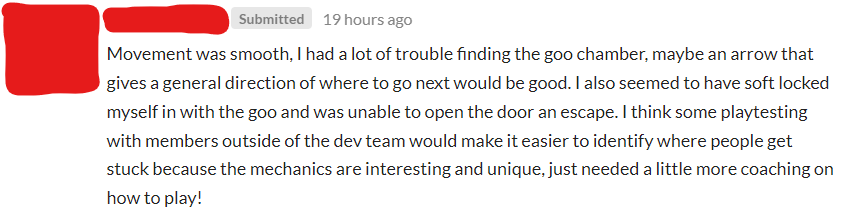

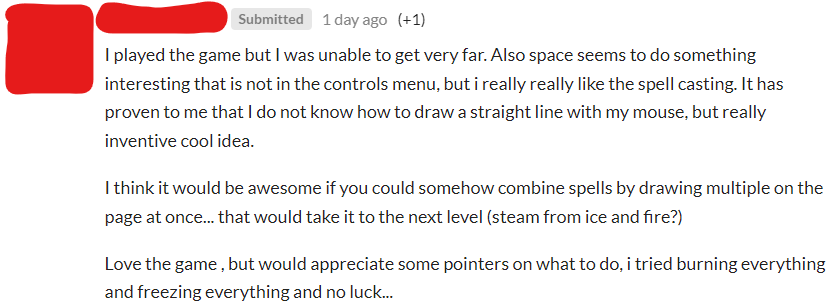

Feedback from people who played the game seemed to be mixed, with most people commenting on the interesting mechanics and liking the overall style, but finding the game to be too confusing or the goals to be poorly communicated. I definitely agree that the aim of the game was not clear enough, and the game should definitely had a tutorial, or at least more instruction on what to do. If I could go back, I would add an arrow on the UI to point the player to where they need to go. Here are some comments left by players:

From these, it is very clear that players are not given enough instruction to play the game.

From these, it is very clear that players are not given enough instruction to play the game.

The way temperature spreads around the goo is definitely functional, but I would have liked for it to be more dramatic, where heating the goo spreads it throughout other goo tiles, instead of just blurring it. If I had more time, I would have fine tuned the shaders and experimented with different functions to make the goo feel more like a liquid.

The game definitely has potential to have more levels, and it would not be very difficult to add more, but for the scope of the jam we decided to limit it to one level as most of out time was spent either coding or making art assets.

In terms of performance, using space partitioning to improve the performance of checking statics for goo would be a great addition, and I think would resolve the stuttering the game sometimes suffers from.

If you have read to this point, thank you for spending the time to learn about the game!